Groff Conklin was one of the most important Science Fiction Anthologists of the 1950s and 60s. He produced dozens of Anthologies in the 1950s, which were widely distributed and found their way into most libraries. Many people discovered Science Fiction through Goff Conklin’s collections.

Groff Conklin was one of the most important Science Fiction Anthologists of the 1950s and 60s. He produced dozens of Anthologies in the 1950s, which were widely distributed and found their way into most libraries. Many people discovered Science Fiction through Goff Conklin’s collections.

Possible worlds is divided into two parts. There are four stories in a section called The Solar System and four stories in a section called The Galaxy. The stories are not great with a few exceptions. The bad stories are The Enchanted Village by A.E. Van Vogt, Not Final! by Isaac Asimov, Limiting Factor by Clifford Simak, and The Pillows by Margaret St. Cloud.

Asleep in Armageddon by Ray Bradbury, In Value Received by H.B. Fyfe were mildly entertaining, but not outstanding.

Asimov’s story is a typical Campbell gadget story from Astounding, but it was written by a very young Isaac, and it flounders, going nowhere (I’ll bet that John W. Campbell wrote the last page or two of the story, because it changes style). The Van Vogt and St. Cloud stories are weak stories without much in the way of character and plot. The Margaret St. Cloud story was a disappointment because I have always felt that she was one of the best short story writers of the Golden Age. Ray Bradbury’s Asleep in Armageddon was poorer than average Bradbury, mainly because the resolution, although chilling, was not that satisfying. I liked In Value Received by Fyfe, but it was such a typical Astounding engineering story, that I barely remembered it a day later. The Simak story is just a bunch of interesting engineering ideas and then the story is over.

On the other hand, the Murray Leinster story, Propagandist, was wonderful, although very much in the same vein as First Contact, my favorite Leinster story. The Malcolm Jameson story, Lilies of life, I had read before in the pages of a 1945 Astounding in my collection, and it is an unexpected concept story concerning environmental science and religion, although ultimately just another technology story.

The Space Rating by John Berryman was an engineering story, but it dealt with a management issue that involved some interesting characters so I would say it was a good, if not great.

Lastly, the Poul Anderson story, The Helping Hand, in my opinion should be required reading in high school civics and history classes. It fails a little in that its plot is mostly just a narrative of events and hardly involves more than a personal conflict, which is not resolved by direct action at the climax. Its subject is very significant, though. I read this in a 1950 Astounding a few years ago and I may have even blogged about it because I was so impressed. I may take the time to analyze it in a future post, but suffice to say, the story treats a conflict of cultures in a way that we all could learn from, especially now when the world is so small.

The stories are all long, as were most stories in the golden age, and average around 9 to 10 thousand words each. The general plot, in almost all cases, is to posit a technical question and let humans solve it through careful analysis, even if they fail eventually. These types of stories filled the pages of Astounding, Planet Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. Groff Conklin must have searched these old pulps for stories and it seems that his criteria was to find inexpensive stories with a few good ones by greater names. The anthology was published in 1955, but most of the stories were originally from 1940 to 1950. Not Final! would never have been anthologized if it were not written by a young Isaac Asimov and the Van Vogt story was much like any other Van Vogt story, only less so. I don’t know where Bradbury anthologized Asleep in Armageddon, but it was not in any of the books that I read in October.

Conklin adds a short preface to each story, which is mostly useless as an introduction and could have been left out. I might have liked a short essay on why he thought these stories important enough to be anthologized, but I would guess that Conklin was just looking for enough inexpensive stories to fill the book and wasn’t interested in the quality.

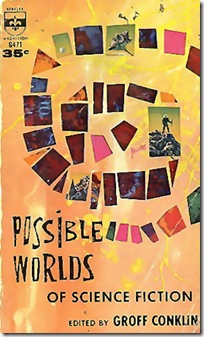

I own both the 1955 and 1960 editions of this book. The image above is the 1960 edition, which I carried around with me on the bus because it was less fragile than the older book.